Closing the Loop on Big Data… One Beer at a Time

Computers serve as powerful tools for categorizing, displaying and searching data, but they’re only the medium for big data.

“We really need people to interact with the machines to make them work well,” says McFarland-Bascom Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Discovery Fellow Rob Nowak in WID’s Optimization research area.

Unlike machines, people work at a finite speed and at rising costs. Nowak wants to improve interactive systems that can optimize the performance of both humans and machines tackling big data problems together.

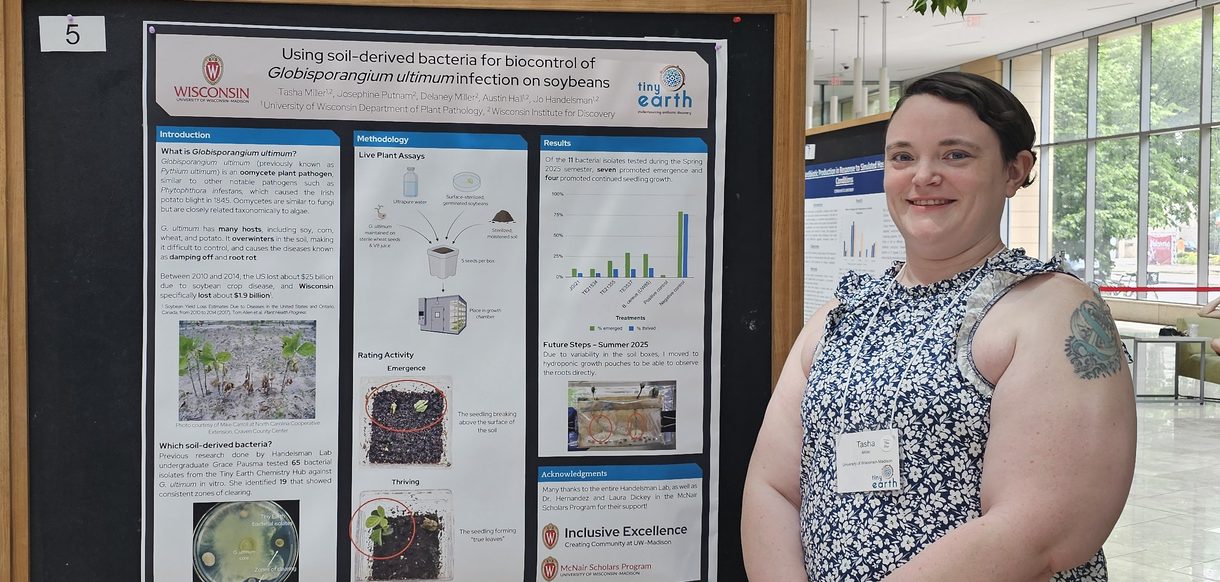

Rob Nowak and Kevin Jamieson testing the app.

Typically, human experts — people who categorize data — will receive a large, random dataset to label. The computer then looks at those labels to build a basis of comparison for labeling new data in the future. Nowak suggests the model should be flipped. “The machine gets the set of examples, then asks a human for further classification of a specific set of data that it might find confusing.”

With support from the National Science Foundation and Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Nowak has been exploring an active learning model, in which the machine receives all the data up front. Initially, the machine makes very poor predictions, improving as a human expert supplies clarifications for confusing data.

To explore these sorts of human-machine interactions, Nowak and graduate student Kevin Jamieson have applied the idea to a technology that’s a natural fit in Wisconsin — an iOS app that can predict which craft beers a user will prefer. Using data gleaned from searching through thousands of beer reviews on RateBeer.com, the researchers’ algorithm presents the user with two beer options, then has that person choose his or her preference, slowly winnowing the options down toward to the user’s ideal beer.

“Basically, if I already know that you prefer Spotted Cow to Guinness, then I’m probably not going to ask you to compare Spotted Cow to some other stout,” says Nowak. “Because there are relationships between every beer, I don’t have to ask you for every comparison.”

“We have big data infrastructure. What we don’t understand is how to optimally yoke humans and machines together in big data analyses.”

— Rob Nowak

These sorts of “this-or-that” determinations tend to be more stable than categorizations based on ranking scales or other more subjective measures, which are more vulnerable to psychological priming effects and can change over time. The finer-point comparisons from humans offer the machine more reliable data to improve its categorization and prediction abilities.

And most importantly, these comparisons allow machines to process data much, much faster, since they require less human help to categorize the data. Nowak says the app can make a personalized beer recommendation based on only 10 to 20 comparisons. That sort of efficiency becomes important as data sets get bigger and human labor can’t keep up.

“There’s no research to be done on the infrastructure side,” he says. “We have big data infrastructure. What we don’t understand is how to optimally yoke humans and machines together in big data analyses.”

— Mark Riechers, UW-Madison College of Engineering