Researchers Look to Control Organ Function Through New Computational Model

The human body’s nervous system is complex. Consisting of the brain, spinal cord and sensory organs, the nervous system acts as the communicator of the body, receiving information, deciding what information to deliver and sending messages to organs to take action. At times, these messages may not be delivered properly due to damaged nerves, causing organ dysfunction. Understanding nerve activity, particularly in the urinary tract, can make it possible to improve the efficiency of stimulation technology to restore bladder function and ultimately improve people’s lives.

Through the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Stimulating Peripheral Activity to Relieve Conditions (SPARC) program, researchers from five institutions across the nation have received more than $1 million in funds to create a computational model using machine learning that can guide the development of new therapeutic electrical signal stimulations and effectively identify a nerve that can control the bladder. John Yin, a professor at the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery and the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, is a collaborator on the project.

Bladder dysfunction, or urinary incontinence, is more common than most think. It affects about 50 percent of women and 25 percent of men. It is also seen more often in women over the age of 50 or women who’ve recently given birth.

“The problem with the nervous system is that it is immensely complicated. Current experiments are more of a trial and error. We want to find a way to be more efficient and reduce animal testing,” said Zachary Danziger, assistant professor of biomedical, materials, and mechanical engineering at Florida International University and principal investigator on the project. “Take, for example, mechanical engineering. Engineers don’t build multiple buildings and see which one stands. We want to be able to know exactly which nerve to use to get an organ to do what we want.”

Danziger adds that the mathematics of the nervous system doesn’t make it any easier.

“We don’t have these fundamental principles to look to. The nervous system is difficult to predict because of its many complex interactions. If we target a specific nerve, we don’t know what else can happen or how other nerves might react.”

The multi-institutional team is using machine learning to connect individual mathematical equations developed by scientists. During the first year of the research, the team will take an inventory of existing mathematical equations that link to physiology and the lower urinary tract system.

Taking these equations and developing algorithms to allow computers to predict how the lower urinary tract system will function when external stimulation is introduced will be managed by Giovanna Guidoboni, professor of electrical engineering and computer science and professor of mathematics at the University of Missouri. Professors of electrical and computer engineering Deniz Erdogmus and Sumientra Rampersad from Northeastern University will contribute machine learning and computational modeling expertise to the joint effort.

“The possibility to stimulate the neurological system from the outside would allow a person to regain control of that activity, which would really improve the quality of life for many people. That comes after you gain the understanding of what to do. Our project is aimed at trying to provide this understanding,” said Guidoboni.

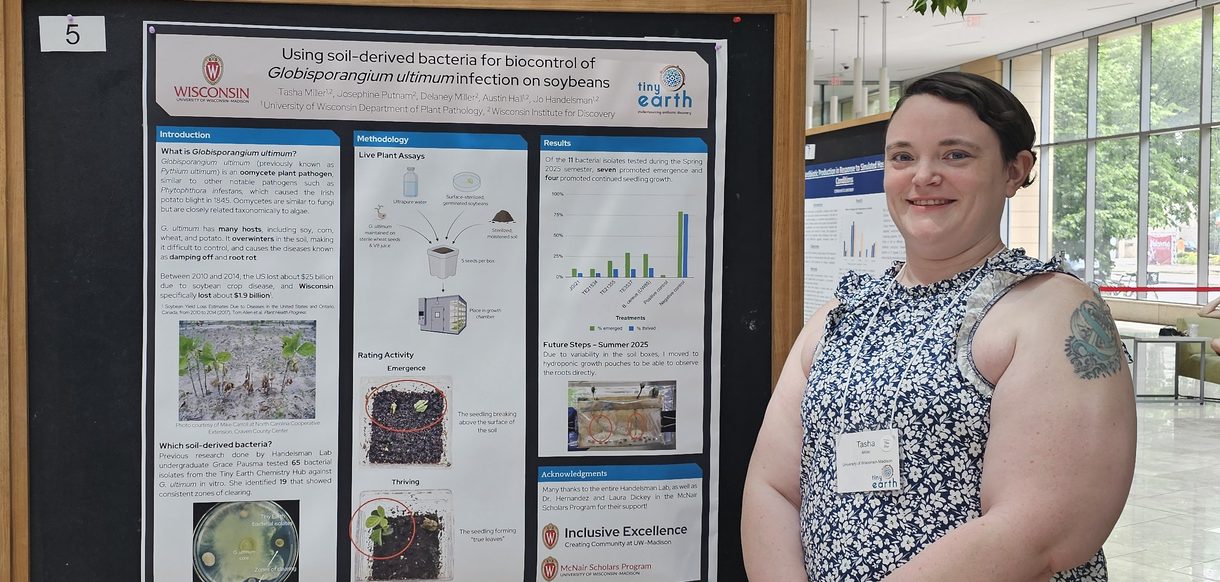

John Yin

At the end of the two years, the team will have developed a new modeling framework—which, through biophysics models and machine learning, can emulate an entire organ system.

The interdisciplinary team is composed of mathematicians, computer scientists, engineers and experimentalists from various institutions: Danziger at FIU; Guidoboni from the University of Missouri; Erdogmus and Rampersad from Northeastern University; Elie Alhajjar at the United States Military Academy; and Yin at UW–Madison.

All involved met virtually through NIH’s 2020 SPARC Ideas Lab, a four-day conference inviting individuals to bring their innovative ideas to the table when it comes to transforming the future of bioelectronic medicine.

“An exciting and unprecedented feature is that our collaboration was conceived and is being carried out entirely online,” said Yin. “We are part of a big experiment that points toward the future of collaborative science and engineering.”