UW Carbone Scientists Present at Annual Cancer Research Conference

All told, over 60 UW Carbone researchers will present their work, with dozens more attending to learn about current advances in understanding and developing treatments for cancer.

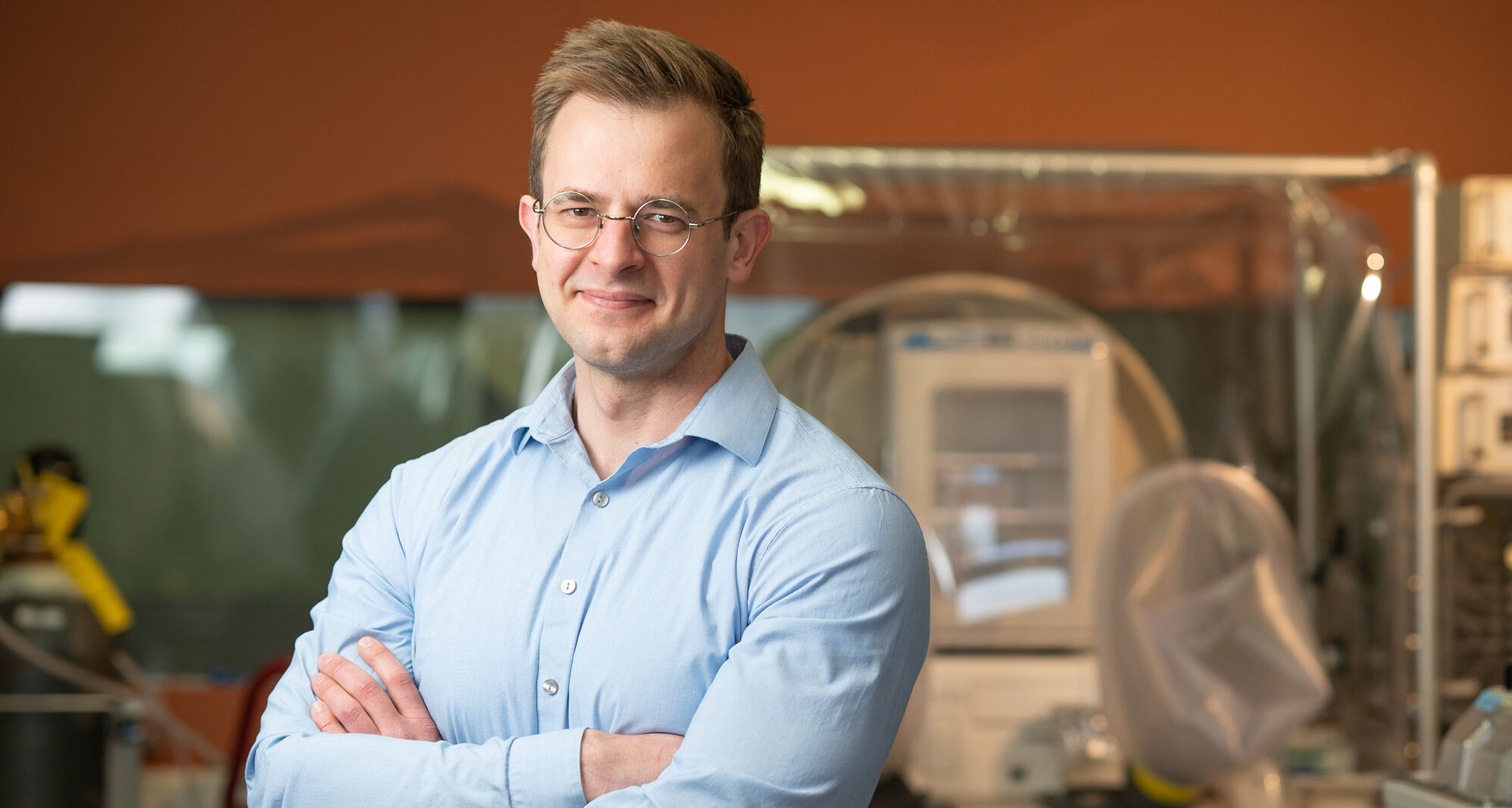

One of the UW Carbone Cancer Center members presenting is Peter Lewis, PhD, of the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery. His work focuses on how genes are turned on and off during embryonic development, and how misregulation in those genes can lead to some childhood cancers.

“In most adult cancers, tumors arise from decades of hits to tumor-promoting genes, and in the right context those mutations can lead to cancers,” Lewis said. “But of course children don’t have decades to accumulate mutations, so how do children get tumors early?”

Peter Lewis

Lewis studies how mutations in DNA-organizing histone proteins lead to cancer development. For example, in one type of pediatric brain cancer, 85 percent of all tumors have one histone mutation in common. Lewis and his colleagues have shown that, if present at the right time in development, this histone mutation prevents proper gene regulation and causes the stem cells to remain “stuck” in stem cell form, leading to cancer formation.

“Most of us get past this window and develop normally, but the children who get these cancers seem to acquire the histone mutation in these specific cell types and in the right developmental window,” Lewis said. His work has implications in comparing pediatric cancers to those of adults, as well as better understanding early developmental mechanisms in humans.

Lewis presented at a broader educational session on Saturday, April 14, and at a research symposium today. Also today, cellular and molecular biology graduate student Adhithi Rajagopalan, a student in the lab of Jing Zhang, PhD, at the McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, will be presenting in a scientific session focusing on animal models of cancer. Their collaborator, UW Carbone physician-scientist Fotis Asimakopoulos, MD, PhD, is co-chairing the session.

Rajagopalan will present on a new mouse model of advanced multiple myeloma. Multiple myeloma is a cancer of plasma cells in the bone marrow, and represents 15 percent of all blood cancers. In the initial phases of the disease, patients are typically asymptomatic. By the time symptoms arise – including anemia, bone pain and kidney disease – patients are in the late stages. Advances in therapies have helped extend survival times by driving the disease into remission, though there is no cure for multiple myeloma.

“It’s important to have some model way to study this disease in the advanced stages,” Rajagopalan said. “Because currently, we don’t fully know what disease mechanisms exist in the later stages or how we can better treat patients.”

A mouse model of early-stage disease exists, but not the advanced disease. Rajagopalan and co-lead author Zhi Wen, a scientist in Zhang’s research group, bred mice from the existing myeloma model with mice that harbored a second mutation in the Ras gene. Ras mutations are found in 45 percent of all advanced myelomas, but rarely in early-stage disease, suggesting the mutation plays a role in driving the later stages.

“In these mice, we can recapitulate much of the human disease,” Rajagopalan said. “This model now serves as a platform to test existing and potential therapeutics for many advanced multiple myeloma patients.”

AACR’s annual meeting covers the latest basic, translational, clinical, and prevention-focused cancer research, including important areas such as early detection, cancer interception and survivorship in all populations. This year’s conference is being held in Chicago April 14-18.

This article originally appeared at med.wisc.edu.