WID Researcher Looks to Break Conversion Rate of Stem Cells

With a simple skin biopsy, scientists can reverse-engineer a few of your skin cells and create genetically identical stem cells called induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Take it a few steps farther, and those scientists can turn your iPS cells into many different cell types to test drug therapies and study your specific genetic information.

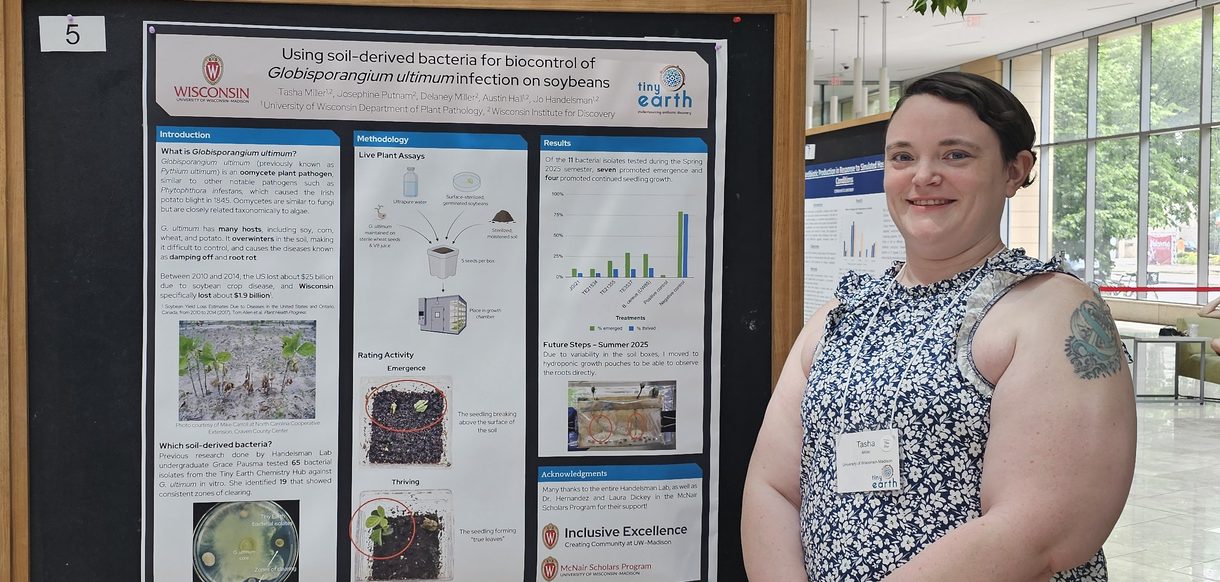

What’s slowing the process down, however, is that only about 1 percent of your cells make the transition to iPS cells, while the rest stall somewhere along the process like a broken down car on the highway. That’s why Rupa Sridharan, WID scientist and assistant professor of cell and regenerative medicine in the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health (SMPH), is so interested in the mechanics of pluripotency.

“Cell reprogramming is interesting to me because among most of the cells, even if they have the capability because I have introduced all the reprogramming factors and I know all the cells in the population express it, there’s still a heterogeneity. Only a small fraction of the cells convert to iPS cells,” said Sridharan, who works in WID’s Epigenetics research group. In addition, she is a recent Shaw Scientist award winner, a distinction chosen by the Greater Milwaukee Foundation.

Rupa Sridharan

So why do the cells stall? And are they all stalling at the same point, or are there several stages where the process is halted? That’s what drives Sridharan. What is clear is that these partially reprogrammed cells are no longer expressing the genes of their old cell type, but they’re not yet expressing some genes necessary for iPS cells, what Sridharan calls the “pluripotency network.”

“There are epigenetic barriers in this partially reprogrammed stage, so what I’m trying to do is to convert one epigenetic modification at a time to figure out what is the most important one, or to find if there is a particular modification that is on top of the hierarchy, so that if I change this one chemical modification, does it cascade and conversion to iPS cells follows,” she said.

Even at the speed of one gene at a time, Sridharan and her lab are well on the way, it seems, to understanding at least some of those barriers. One project still in progress is showing promising results, significantly elevating the standard one percent cell conversion rate through the introduction of just a few small molecules.

“We’re trying to dissect how each of these molecules is destroying this barrier,” she said. “The interesting thing about these small molecules is that they act synergistically,” she said.

As a Shaw Scientist, Sridharan received $200,000 in unrestricted research support.

“It was exciting and a great relief at the same time. I am a new assistant professor and a lot of my time has been spent writing grants. It’s really nice to get one as prestigious as the Shaw Award. I have an excellent mentoring committee here. I’m also very fortunate to have a very interested and hard-working lab,” she said.

— By Ian Clark, UW Health