Wisconsin Instructors Engaging Students in the Fight Against Antibiotic Resistance

Confronting the antibiotic resistance crisis is a formidable undertaking. But one answer may lie in addressing another challenge simultaneously. During the second week of January, more than two dozen biology, microbiology, cell biology, and related course instructors from schools across the state and country came to the University of Wisconsin–Madison to become part of a program that utilizes a curriculum designed to retain and engage science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) majors with a course built around antibiotic discovery.

The use of antibiotics has revolutionized human health, but our supply of effective antibiotics is dwindling as pathogenic bacteria evolve resistance to them. Meanwhile, discovery and development of new antibiotics that are safe and effective for human use has not kept pace with emerging resistance. As a result, infections that are untreatable using available antibiotics are on the rise and the threat of widespread “superbugs” looms.

As the antibiotic resistance crisis intensifies, the scientific community faces another challenge: according to a 2012 White House report, the United States is on pace to fall one million STEM graduates short of the number needed to fulfill economic demands. The report notes that fewer than 40% of students who enter college intending to major in a STEM field complete a STEM degree.

At the time of the report, professor Jo Handelsman, now Director of the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, saw an opportunity to improve retention in STEM degree paths while simultaneously combatting the antibiotic shortage. Based on the report’s recommendation that instructors replace traditional laboratory courses with discovery-based research courses, Handelsman designed the Molecules to Microbes curriculum while at Yale University (which is now being implemented as Tiny Earth).

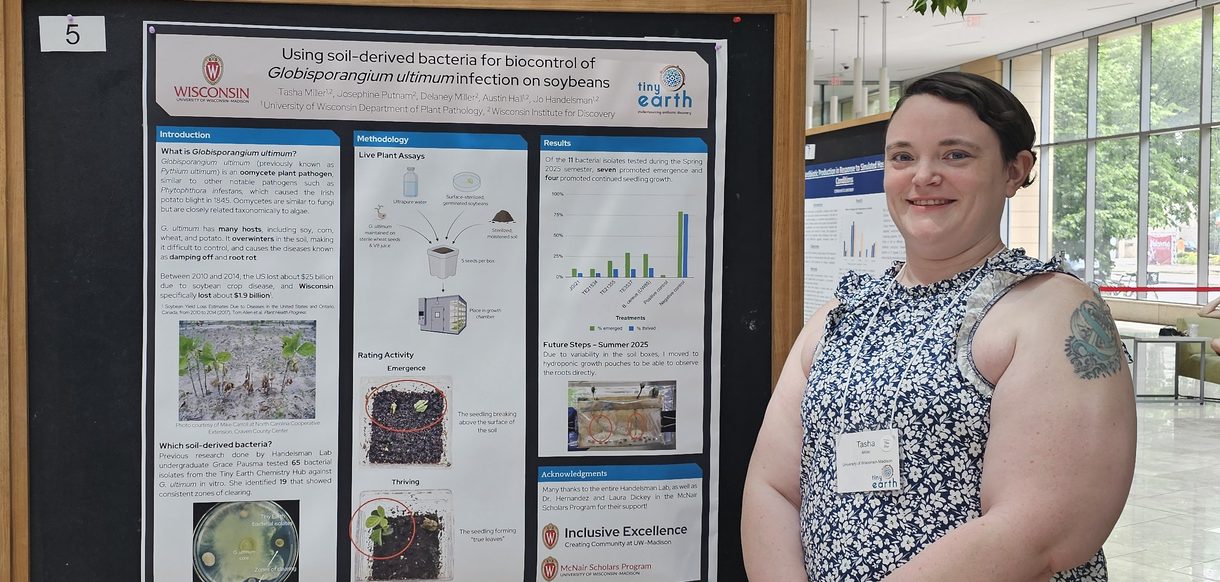

During a semester of the curriculum, students—usually college freshmen and sophomores experiencing a research lab for the first time—isolate and characterize bacteria from soil samples while learning introductory biology content, lab techniques, and research methods. The bacteria the students isolate from soil found in their local environments could lead to novel antibiotics—after all, more than two thirds of antibiotics originate either from bacteria or fungi found in soil. Courses like Tiny Earth are more likely than traditional lab courses to keep students interested in STEM by turning them into scientists through a hands-on, real-world laboratory experience. And, Tiny Earth turns student scientists into an army of researchers searching the soil for solutions to the antibiotic crisis.

Since its foundation in 2012 at Yale, Handelsman’s pilot has grown exponentially and globally: the curriculum has now been implemented at over 250 institutions in 14 countries and 40 U.S. states. In 2018, the initiative found a new home at UW—Madison’s Wisconsin Institute for Discovery as Tiny Earth, and the state of Wisconsin is becoming the epicenter of the network. This January, instructors from five 4-year and three 2-year UW System schools, five technical colleges, one private university, and one Wisconsin tribal college gathered in the Discovery Building at UW–Madison to become partner instructors. The week-long training covered the entire research curriculum over many hours in the building’s teaching laboratory. Considerable time was also spent placing the course within the pedagogical framework of scientific teaching, ensuring that the instructors will be able to teach the course with confidence and provide an engaging learning experience for students.

Training instructors Nichole Broderick of the University of Connecticut and Debra Davis of Wingate University led the 29 newly-recruited instructors through the curriculum and welcomed them to the network of partner instructors. The network shares ideas and best practices and helps new instructors determine how best to implement the course at their institutions. Throughout the week, trainees connected with experienced instructors via video conference, learned from expert instructors, and had the opportunity to meet and hear from founder Jo Handelsman.

The instructors from UW-Parkside, UW-Eau Claire, UW-Green Bay, UW-River Falls, UW-Whitewater, UW-Fond Du Lac, UW-Waukesha County, UW-Rock County, Northeast Technical College, Northcentral Technical College, Lakeshore Technical College, Madison College, Milwaukee Area Technical College, and Marian University were recruited by Sam Rikkers, executive director of Tiny Earth, to engage the state of Wisconsin. “Extending our program’s power of discovery-based learning across Wisconsin puts Wisconsin students at the forefront of the army of student scientists tackling one of the most critical public health crises of our day,” says Rikkers.

Rikkers was also keen on partnering with institutions reflecting the diversity of the United States. January’s training included instructors from three Historically Black Colleges and Universities represented by Howard University, Mississippi Valley State University, and University of Maryland Eastern Shore; two tribal colleges in the College of the Menominee Nation and Fond Du Lac Tribal and Community College; and Sacramento State University, a Hispanic-serving institution. “A diversity of student scientists, like a diversity of soil samples, only enhances discovery potential and impact,” says Rikkers.