Co-Zorbing: The New Frontier in Bacterial Cooperation

The ability to form communities is essential at all levels of existence. Whether building a town, finding like-minded people, or fostering shared beliefs, these connections create strength and empowerment. Even the smallest communities lay a foundation that supports and uplifts others, driving collaboration and growth on a larger scale. The same holds true in microbial communities, which can take on unexpected forms—like biofilms, a remarkable example of bacterial cooperation.

“Biofilms are sticky structures that are formed by microbes and you can see them everywhere. Your teeth, your sink if you haven’t cleaned it in a long time. Medical devices, and plant roots, and on rocks in rivers and streams,” says Shruthi Magesh, a graduate student in the Jo Handelsman lab at the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery (WID).

Biofilms are usually stationary. In a recent study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers discovered that biofilms made of a specific type of bacterium called Flavobacterium johnsoniae can form 3-D structures that are capable of moving. Not only do these structures move, but researchers have discovered they can move other species of bacteria, too.

Shruthi Magesh

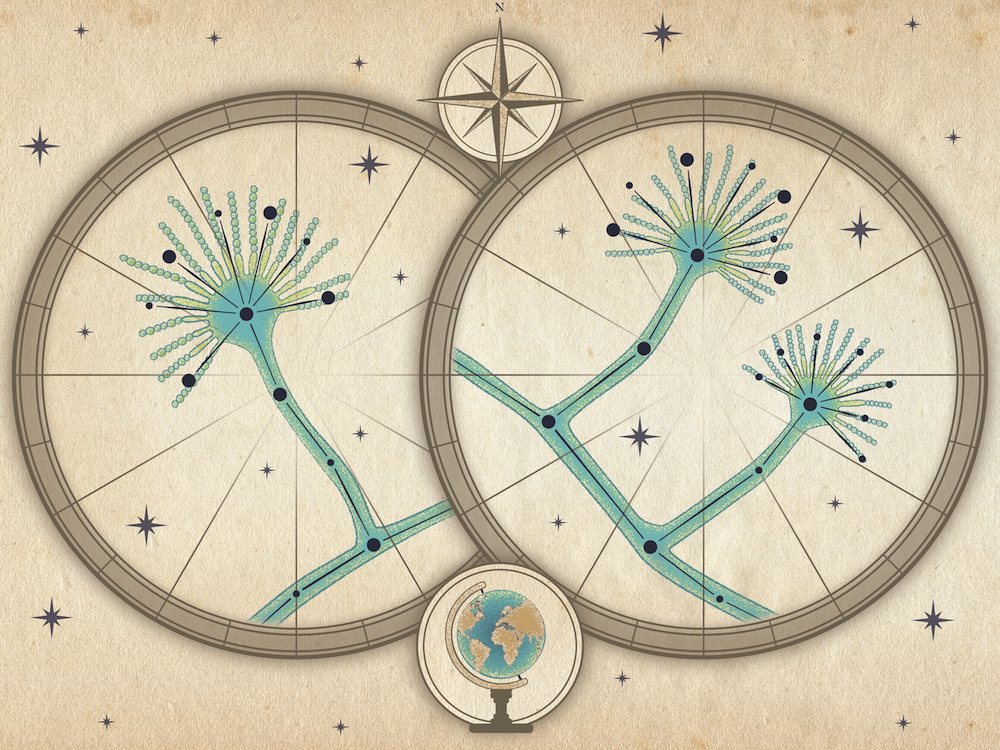

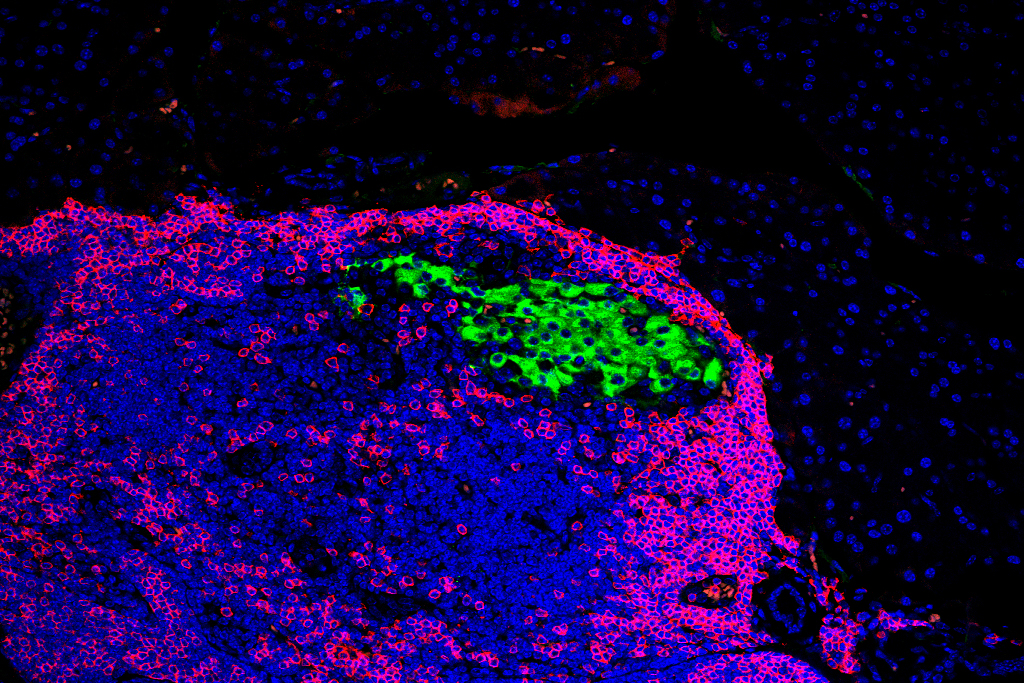

Found in soil and freshwater, F. johnsoniae can create a moving, spherical biofilm called a zorb. This naturally forming zorb moves not with the use of external appendages, but thanks to its base cells and a core made of large carbohydrate molecules. Zorbs have been observed for, but Magesh observed that zorbs can also form co-zorbs, or organized, multispecies, motile biofilms that contain a core-like structure. F. johnsoniae cells aggregate around other bacterial species and transport them. Thus, F. johnsoniae provide stationary bacteria in their community with means of transport.

“We figured out the Flavobacterium johnsoniae is the active partner that forms an aggregate around the second bacterial species to create these structures, or co-zorbs, that can transport these species and others across surfaces,” says Magesh.

Understanding this cooperation is huge because it could possibly be exploited to help beneficial bacteria. For example, it might help distribute nitrogen in soil or act as a biomolecular vehicle designed to carry and deliver targeted cargo within a living system. To test this hypothesis, the researchers looked at whether zorbs could form in other environments, such as inside organisms.

F. johnsoniae can cause disease in fish, including transparent zebrafish, which serve as ideal hosts for studying zorbs, hence, the researchers used live imaging to observe zorbs and co-zorbs in zebrafish. Magesh, along with scientists from the David Beebe lab and in collaboration with the Anna Huttenlocher Lab, found that the co-zorbs formed and moved inside the zebrafish larvae, just as they did in the lab, revealing a new way bacteria move inside living things. Researchers observed that both E. coli and S. aureus bacteria moved faster with F. johnsoniae in co-zorbs than alone. This shows that F. johnsoniae can form mobile biofilms with different bacteria and keep them organized in complex environments like the zebrafish brain.

Nature has a few examples of interspecies biofilms, but these behaviors depend on either single-cell motility, called hitchhiking, or interspecies expansion in which individual cells carrying non-motile bacteria grow and expand to spread across surfaces to form multispecies biofilms.

The discovery of co-zorbing behavior in F. johnsoniae provides a fascinating glimpse into the cooperative dynamics of bacterial communities. This behavior not only highlights the intricate interspecies interactions, but also enhances our understanding of bacterial organization and mobility. By shedding light on the role of biofilms in bacterial transport and the adaptability of microbes in diverse environments, this study opens new avenues for exploring microbial ecology and potential applications in biotechnology.

–Laura Red Eagle

Link to Movie video (Movie S2): https://uwmadison.app.box.com/s/pdtamhp3w8y2b9f64jzrklrup1e6zyss

Link to paper: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2417327122

Contact: Shruthi Magesh, magesh@wisc.edu

This study was supported by the US Army Research Laboratory and the US Army Research Office under Contract/Grant W911NF1910269. J.S. was supported by National Institutes of Health grant T32GM135066-05. N.M.S was supported by National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program grant DGE-2137424. J.S, C.L, D.J.B were supported by National Institutes of Health grant NIH P30CA014520. A.H was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R35GM118027.