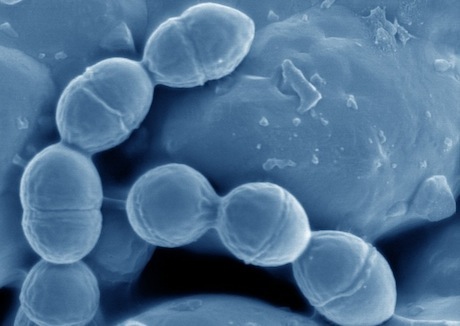

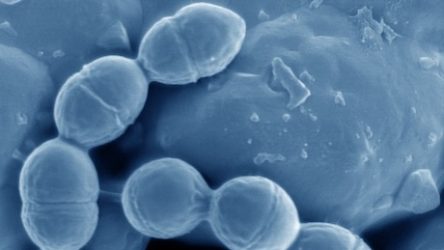

What do a badger, milk, kringle, and polka music have in common? They are all Wisconsin-designated state symbols. Wisconsin is famous for its cheese, but the real hero remains overlooked: the state’s flagship industries would not exist without a certain hardworking yet under-recognized microbe. The humble bacterium known as Lactococcus lactis, or L. lactis, is routinely used for fermenting foods such as cheese, buttermilk, sour cream, and kefir. It is also essential for adding flavor to Wisconsin staples like beer, sauerkraut, and wine. Last but not least, this little hero produces nisin, which is a natural antimicrobial that can protect against infection in burn wounds and pathogens such as staphylococcus and listeria.

Cheesemakers add L. lactis bacteria to milk to convert lactose, the sugar found in milk, into lactic acid. This lactic acid is what causes milk to coagulate and form the curds that over time become delicious cheese, and a lot of it: To date, Wisconsin is the world’s largest producer of cheddar cheese, manufacturing more than 7 million pounds thanks to the help of L. lactis. Additionally, various strains of L. lactis are responsible for other resumé-worthy cheeses, such as Camembert, Roquefort, Brie, blue, cottage, and cream cheese. It’s no wonder that the microbe is feeling bleu about its lack of recognition as Wisconsin’s hardest working microbe.

Bringing awareness to this oversight is the UW group Catalyst for Science Policy (CaSP), housed at the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery. “Microbes are amazing, and aid in so many different parts of our life, like gut health, food production and so much more. Having a state microbe would show how invested the state is in scientific research and biotechnological innovation, but also that we care about our state’s unique scientific and cultural heritage,” says Austin Hall, CaSP member and plant pathology PhD student. Adopting a state microbe would provide a unique science outreach opportunity to educate the public about the vital role of microbes in the Wisconsin economy and dairy industry.

Since the mid-1800s, the art of cheesemaking in Wisconsin has formed a fundamental pillar of the state’s economy. One pioneer of this craft was Charles Rockewell from Fort Atkinson, who is documented as one of the earliest cheesemakers in 1837. By the 1930s, what was once a handful of individual cheesemakers had multiplied to over 2,800 grade-quality cheese factories, Wisconsin being the first state to implement a system for grading cheese quality. Wisconsinites went on to develop unique cheeses, including Cupola, Muenster, Marble Blue-Jack, Colby-Monterey Jack, and BellaVitano cheese.

It’s no secret that Wisconsin agriculture is a major economic driver in the state, accounting for 11.8% of the state’s employment and contributing $104.8 billion to the state economy. The dairy industry alone contributes $45.6 billion to the state economy each year. “Wisconsin’s largest industry is agriculture, and half of that is dairy,” said Dr. Ken Todar, emeritus professor of bacteriology, “and half of that is cheesemaking. Without L. lactis, there would be no state cheese and a much smaller cheesemaking footprint in the world.”

There is a reason “America’s Dairyland” is the number one cheese producer in the country, producing 3.47 billion pounds of cheese in 2021 and accounting for 25% of the country’s cheese production. More than 1,200 licensed cheesemakers manufacture more than 600 varieties of cheese, nearly double the number of any other state, all made possible by one trusty microbe. It is time for L. lactis to be acknowledged.

In 2009, legislation designating L. lactis as the Wisconsin state microbe passed the assembly, but was not taken up by the senate. But the original idea caught on, and since this initial effort, several other states have successfully adopted state microbes. In 2013, Oregon became the first state to designate a state microbe, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or brewer’s yeast, which is involved in the production of alcoholic beverages such as beer, wine, and mead, and is vital to the craft brewing industry that generates billions of dollars for the state every year. In 2019, New Jersey approved Streptomyces griseus as its official state microbe. This soil bacteria, discovered in New Jersey in 1943, produces the antibiotic streptomycin that is used to treat several serious diseases. In 2021, Illinois designated as its state microbe the mold Penicillium rubens, first grown in a lab in Peoria, Illinois, and producer of very high amounts of penicillin. But Wisconsin and L. lactis have been left behind.

Like these microbes, the L. lactis bacterium plays an essential role in the economy, culture, and state identity. The designation of a Wisconsin state microbe, such as the Lactococcus lactis, will not only promote scientific awareness and curiosity but also offer distinctive opportunities for science education, outreach, and communication with the general public. This includes engaging students in hands-on microbiology lessons, organizing community workshops, and fostering a deeper understanding of the critical role microbes play in our daily lives, from food production to environmental sustainability. Such legislation would also honor the artistry and innovative legacy of the agricultural and dairy leaders across Wisconsin.

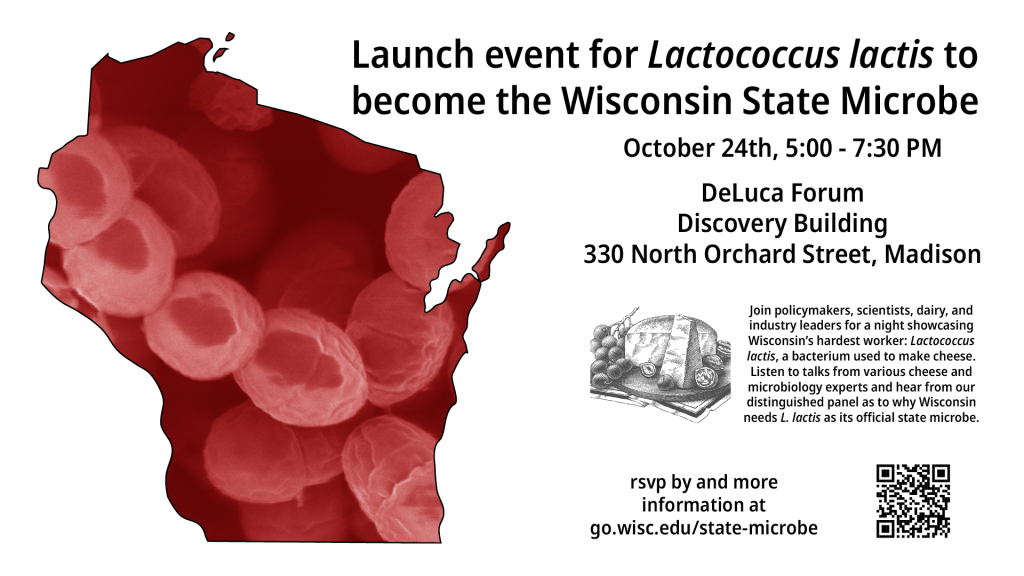

Join CaSP for the State Microbe Recognition Gala on October 24th from 5-7:30 PM at the Discovery Building in Madison, WI, where policymakers, scientists, dairy and industry leaders will discuss their campaign to designate L. lactis as Wisconsin’s state microbe. See flyer for more details and make sure to RSVP by October 20th.

You must be logged in to post a comment.