The difficulty of making big decisions on complex issues is no more apparent than in the day-to-day lives of policymakers. Elected officials, agency employees, and people at all levels of decision-making processes have to sift through competing stakeholder interests, budgets, predictions, myriad variables, and data — often with either not enough information to make reliable prognostications or so much data that it can be difficult to know where to begin.

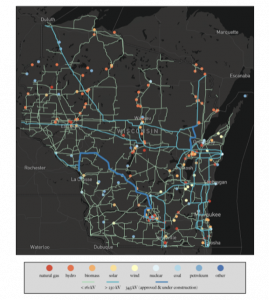

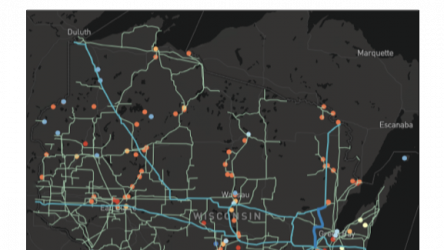

Wisconsin’s energy system is no exception. The energy needs of the state vary in real time, as do the outputs of renewables like wind and solar. Renewables also require initial investments of money, resources, and sometimes land, and storing and transmitting energy relies on complex networks. Weighing these variables and more to make decisions about energy policy in Wisconsin is a daunting task for policymakers.

Researchers at the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery (WID) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison are building mathematical models that can inform decisions about the future of Wisconsin’s energy system. Creating and improving such models has been a central part of Stephen C. Kleene Professor of Computer Sciences Michael Ferris, who leads WID’s Data Science Hub. Ferris is interested in many large scale problems but has recently been focused on energy systems. Developing mathematical models is an important endeavor, but influencing policy is another thing entirely. With a new project, however, Ferris and his collaborators are bringing their models from the lab into the real world.

“We’re trying to get good models… into policy decision-makers’ hands, but in a way that they are able to use them.”

A grant from the Tommy G. Thompson Center on Public Leadership is supporting a project that will put the models developed by researchers directly into the hands of policymakers with tools that are carefully designed to be accessible, user-friendly, and ultimately, useful for making decisions about energy policy. “It’s a bridge to a mechanism to bring mathematical modeling into policy analysis,” says Ferris. “We’re trying to get good models… into policy decision-makers’ hands, but in a way that they are able to use them.”

Doing so, says Ferris, requires input, compromise, and understanding from both the researchers developing the models and decision-makers hoping to use them. “We need to make sure that our models have a user-friendly interface and that they are relevant to the questions that people actually want to ask,” says Ferris, “but also it needs policymakers to step a little bit out of their comfort zone and to think about ways that they are willing to interact with collections of models or different agencies who have impact upon a policy decision.”

The project, called Wisconsin Expansion of Renewable Electricity with Optimization under Long-term Forecasts, or WEREWOLF for short, looks to inform policy years — or even decades — into the future by allowing policy analysts to explore costs and benefits in custom energy scenarios and investments in new energy technologies. The software infrastructure will connect such analysts to the cutting-edge computing and data science technology developed at the University.

Ultimately, WEREWOLF is meant to help develop the Wisconsin energy system of tomorrow, revealing the policy interventions and planning scenarios that make it achievable through dialog between policymakers and scientists. The team currently includes Ferris, Data Science Hub scientist Adam Christensen, and energy policy expert Josh Arnold, but will expand to include more experts from both the modeling and policy camps. “The team has to be diverse so that we can generate real models that are astute and relevant to the questions being answered,” says Ferris.

WEREWOLF is still nascent, but the team is already engaging with the Wisconsin legislature, implementing a prototype model, and getting input from others who have developed interfaces between science and policy about what works and what doesn’t. If successful, WEREWOLF could be a model for how to transform not only energy systems, but also the relationships between researchers and policymakers.

— Nolan Lendved

You must be logged in to post a comment.